Trying to figure out what Javascript Closure’s are is one thing, but determining why we even use them is another. A lot of the posts I come across talk about the closure being an “advanced” technique, and then they walk through how to do it. It may seem a little fuzzy to some while reading through it though, because you don’t know why you are writing a closure.

I’m going to show a brief walk-through of a closure here, but more importantly I will point out why we are doing what we are doing. First of all, we must re-emphasize that Javascript does not have classes in it’s language. Coming from another background, we may be used to defining classes with methods and properties for manipulating our objects. Another feature with classes we enjoy is data encapsulation. This means we are able to hide some data from public use.

I think there are two main points to understanding the How and Why part of a closure, and I’ll go over them here.

1. Scope

2. The Garbage Collector

SCOPE

With Javascript, pretty much everything is up for grabs. Using your Firebug or Chrome DevTools or whatever, it’s easy to inspect an object’s properties. The properties show you the accessible elements of whichever object is being inspected. So for describing a closure, one of the main points we need to understand is Javascript’s scope.

Scope is simply looking at a block of code, and understanding which variables are accessible from you current location. Javascript makes this extremely simple, by only offering us a global scope, and function scope. So any variable we define outside of a function is global. Any variable declared with the var keyword inside of a function is only available within that function’s (and nested functions) local scope (I emphasize with the var keyword, because if you assign value to a new variable without the var keyword it will be assumed global in scope).

This little block of code I’m going to go over here with you covers A LOT of Javascript in just a few lines. The first thing I’m going to do is use an immediate function to instantiate an object in a namespace. All that means is, the only thing I’m making global is one variable.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Test</title>

<script>

var CB = (function () {

var counter = 0;

var sayHi, showCounter;

sayHi = function (str) {

var content = document.getElementById('content');

content.innerHTML = str;

counter+= 1;

};

showCounter = function () {

return counter;

};

return { sayHi: sayHi,

showCounter : showCounter };

})();

</script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="content"></div>

</body>

</html>

This is the entire script for my example, and you can copy and paste it, save it as an HTML file, and open it in your browser.

The first thing I want to go over is the opening and closing of my script:

<script>

var CB = (function () {

. . . .

})();

</script>

Understanding what I’m doing here is extremely important. I’m assigning a variable to an immediately invocable function. What that means is that the CB variable is going to be what this function returns, because the function is executing during the assignment. So what CB actually is, is an object as we can see from the return statement:

return { sayHi: sayHi,

showCounter : showCounter };

So I’m returning an object, as defined by the {curly brackets’ } literal declaration. Inside that object, are two methods which point to the two functions I declared and assigned to the local variables with the same name.

The reason I wanted to assign a function that returns an object, and not just an object is because of the scope. Let’s take a look at the CB initial function’s local variables.

var CB = (function () {

var counter = 0;

var sayHi, showCounter;

There are three local variables being defined here. The first variable appropriately named counter is a counter, that I assign to zero. The next two variables are going to be the methods I want to create for my new object.

So you can see in the main function, I assign the last two variables to the same named properties of the returning object. Let’s look at the functions, then see how they work.

sayHi = function (str) {

var content = document.getElementById('content');

content.innerHTML = str;

counter += 1;

};

The first function (sayHi) modifies an HTML element with a string passed to it, and increments a counter. The counter here is the important thing to see, as it is the essence of our closure. sayHi is defined as a function, so it is creating a new scope for us to work in. I do not define counter with a var statement inside the function. So looking up the object hierarchy chain, the function steps up in scope to the CB function and finds a declared counter variable. This variable is what is being incremented.

Let’s take a look at how we view the counter, with the second method.

showCounter = function () {

return counter;

};

As above, the showCounter function steps up to the CB function to find the counter variable.

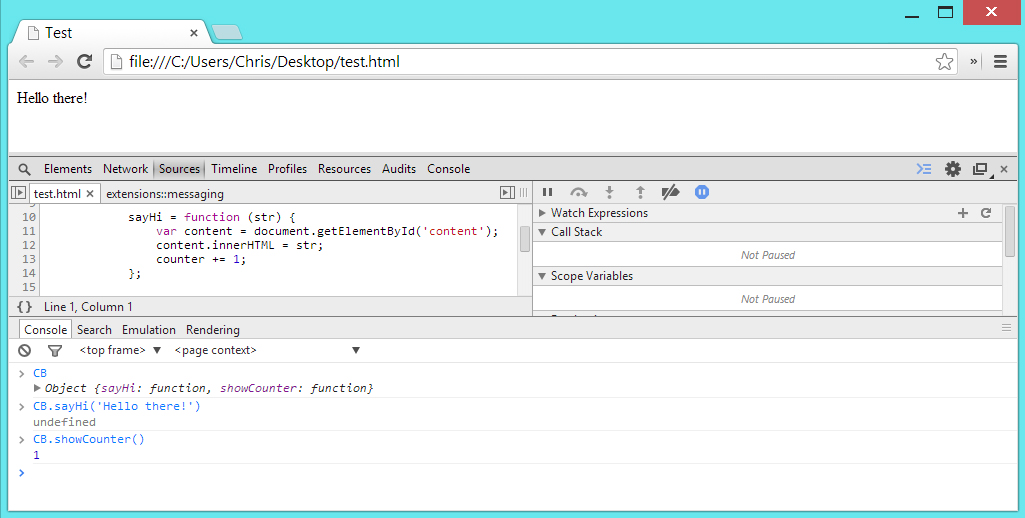

Now since the CB function is immediately executed, all we are left with in the CB variable are the two returned functions. Here’s a look at my Dev Tools immediately after initially loading the web page.

I run three commands in the console after page load. The first command CB simply shows the object that has been created. We have an object with two functions, sayHi and showCounter. Then I ran the first method with a string parameter, and we can see it displayed that string on the web page. Next, I run the method to show how many times I changed the text, and we are returned with the value 1. Let’s change it again.

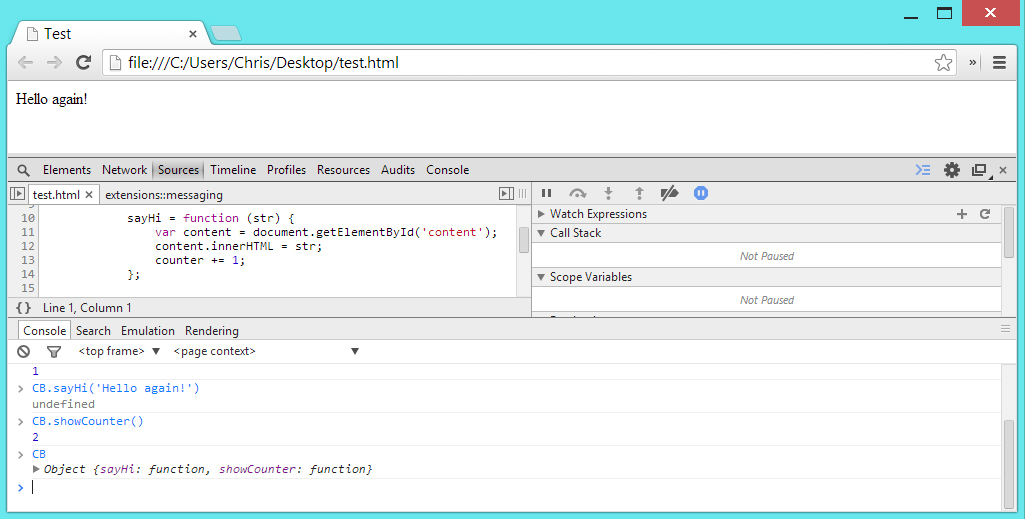

Now I changed the text by calling our first method again, and while doing that incremented the counter. So I call the counter again, and we can see that it has incremented to 2 now.

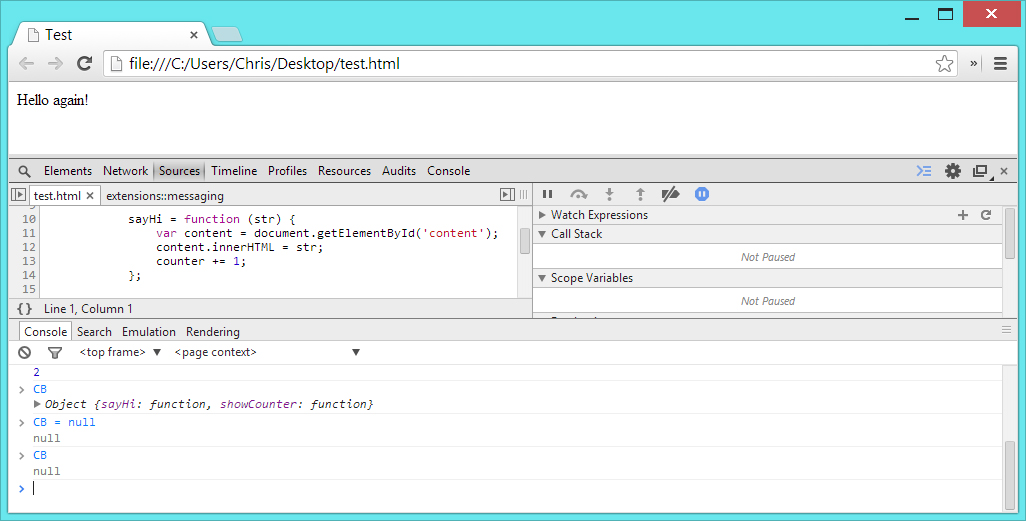

Taking a look back at our CB object, we can see that there are only two properties still. There is no counter variable, but only a method that returns the counter. The counter being returned is the variable that was defined in our original immediately invoked function, and we still have access to it. We still have access to this variable, because of how the Garbage Collector works.

GARBAGE COLLECTOR

Fortunately for us, Javascript utilizes an operation known as the Garbage Collector to help keep our memory environment clean. The Garbage Collector basically reviews items left in memory after a code block executes, and it gets rid of what we do not need. This is great, because it does some work for us that we actually should be doing. Anytime all references to a variable are removed, the garbage collector removes that item from memory. Suppose we are done using our CB object, and we want to remove it from memory. The CB variable is simply a reference in memory that is pointing to our object, so we can tell it to point to nothing, or null.

Here I point the variable to null, and now there is nothing in memory referencing our object. The Garbage Collector came in and removed it from memory. Although we cannot access it from memory since we moved our reference to null, the object is automatically destroyed from memory for this very reason. The same thing happens when a function leaves scope. When a function has finished executing, the garbage collector comes and removes everything that no longer is being referenced. Here’s where the closure comes in.

Here I point the variable to null, and now there is nothing in memory referencing our object. The Garbage Collector came in and removed it from memory. Although we cannot access it from memory since we moved our reference to null, the object is automatically destroyed from memory for this very reason. The same thing happens when a function leaves scope. When a function has finished executing, the garbage collector comes and removes everything that no longer is being referenced. Here’s where the closure comes in.

We are returning the showCounter function as a method of our new object. This function references a variable that was in scope of a function that no longer exists. But there is a reference to that variable, so the Garbage Collector does not destroy it. However, we now also no longer have access to manipulate this data. So essentially what we have, is a private property of an object, which immitates encapsulation in a class in Object Oriented Programming.

So really what I wanted to show in this blog post is not just, “Here’s how we can make a closure”, but I hope I helped clarify WHY we want to make a closure. The benefits we now have are protecting our data from third party code or any manipulation that we don’t desire.